As a linguistic anthropologist, I think a lot about how we relate to written language, not only in different ways from spoken, but in different ways depending on how it’s presented. We often take for granted the existence and significance of something called “books”, when of course what those are and how we read them are matters mediated by any number of cultural factors.

Now classic work by Shirley Brice Heath initiated a complex conversation about how different groups of parents socialize their children into particular relationships with the written word, as they guide them from a young age to understand books as stories, words in their written forms, and letters as representations of sound (to varying degrees of emphasis). These aren’t minor distinctions, as kids are developing understandings about what to look for in a text, and specific forms of literacy (and the types of children who use them) are later encouraged and validated in educational settings.

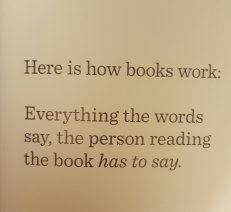

Every night, I read books with my 5 year old son, and I often wonder about the implications of how I’m teaching him to relate to the stories, the words, and the books-as-texts. For the past few weeks, he’s rediscovered a book we bought him a couple of years ago called The Book With No Pictures by B.J. Novak (yes, the dude from The Office). It’s become a favourite (meaning we read it every. single. night. Sometimes two or three times), and every time I come to this page:

…it awakens the latent linguistic anthropologist. Is this how books – and in particular, children’s books – work? Why? How does this relate to our Western sense of texts as authorities, instructor/teachers, or sources of knowledge? The book goes on to adopt two voices – one set of words the reader is apparently being “forced” to say (like “My head is made of blueberry pizza”) and a meta-reader who comments on how frustrated they are to have to read these preposterous phrases (“I didn’t want to say that”, “Please choose a book with pictures next time!”).

It’s a cute book, it makes my five year old crack up every time we read it (Ed: why don’t small children get tired of the same joke? Seriously.), and I’m clearly overthinking it. But there are questions worth asking in there – how do books work? How do we teach children about how books work? And is my head actually made of blueberry pizza, if the book told me to say it, and I said it out loud?